Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

When you encounter a new mathematical concept, it’s not enough to memorize its statement. True understanding comes when you can integrate it into your personal “mental map” of the mathematical universe.

Many people develop this skill gradually. But the purpose of this post is to make that process stable—to understand what actually helps learning stick. We’ll try to unpack what’s happening, often implicitly, when a good mathematician internalizes a concept. And as with many profound ideas, the keys are often simple and subtle: asking good questions.

So, what makes a question “good” when trying to understand a mathematical idea? Here are some prompts that I find helpful:

Try to ground the abstract concept in concrete cases. If it’s an extremal problem, look for sharp examples.

For instance, in graph theory, when you learn a theorem, try to construct an example (or an extremal one) that satisfies the statement exactly. It helps clarify the boundary between what the theorem guarantees and what it doesn’t.

Ask yourself whether the idea connects to something you already know. Does it resemble another concept? Does it belong to a larger family of ideas?

When you first encounter Szemerédi’s theorem on arithmetic progressions, it might feel isolated. But it can be understood through a Ramsey-theoretic lens: in large enough systems, certain patterns become unavoidable.

This often helps identify what part of the statement is doing the real work. In other words, is this theorem proving the strongest form possible? Does a weaker assumption also give what you currently have as the conclusion?

Take the Kovári–Sós–Turán theorem for example, which says if you forbid any bipartite graph, you should get sub-quadratic bound. Then, you ask can I still get sub-quaratic bound if something is not bipartite? However, you realize that it is not possible by looking at Erdos-Stone-Simonovits.

Sometimes it’s useful to ask: if I try to prove this result without the standard machinery, where do I get stuck?

For example, the Prime Number Theorem is hard to approach without the Riemann zeta function. The obstacles pile up quickly. But once you bring in the zeta function, you inherit an entire analytic toolkit—Mellin transforms, Fourier analysis, contour integration—that makes deep results accessible. The abstract setup pays off because we’ve developed so much structure around it.

Try to identify a core insight or a context where the result becomes especially useful.

Take correlation inequalities: you probably don’t remember the general form. But you remember why they’re useful—when you wish two events were independent but they’re not, correlation inequalities give a handle on how much worse the dependent case can be. That’s the kind of intuition you want to carry forward.

Ultimately, understanding a mathematical concept means being able to talk to it—to ask it questions, test its boundaries, and see how it interacts with the rest of your mathematical world. Memorization fades, but good questions build mental bridges that last.

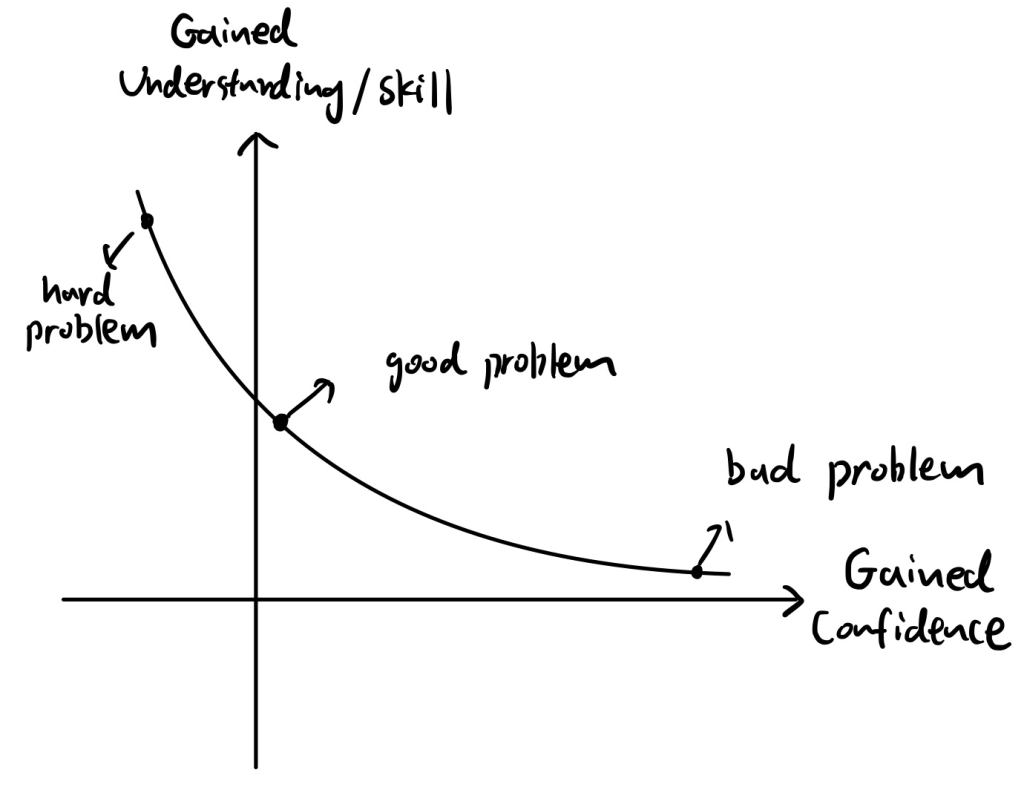

You will encounter a hard problem to discourages your confidence every once in a while, then you need a good problem to keep your confience level while effciently increase your skill level.

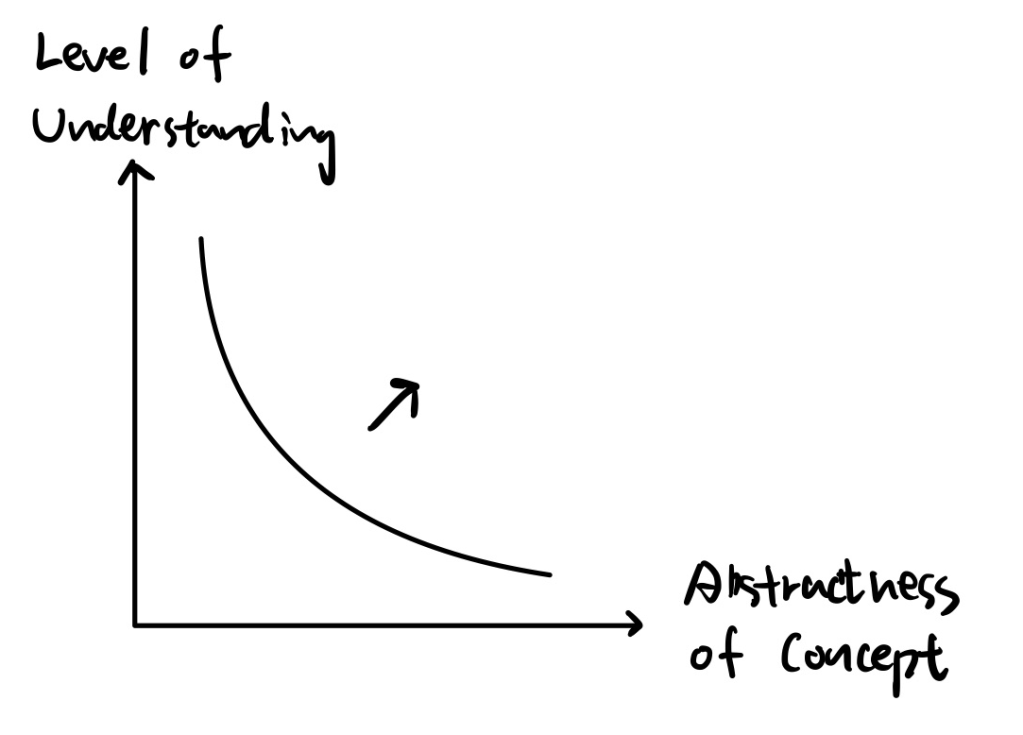

One of the most discouraging parts of learning pure math is the feeling that your understanding drops off as you move into more abstract territory. And that feeling isn’t wrong — in fact, it’s expected. The diagram above illustrates a common truth: as the abstractness of a concept increases, our level of understanding tends to decrease. This doesn’t mean you’re not smart enough. It just means you’re playing the game at a higher level.

The key is to not expect your understanding of advanced, abstract ideas to feel as solid as your grasp of earlier, more concrete ones. That’s normal. The real goal in developing mathematical skill is not to eliminate this curve, but to shift it upward and to the right — in other words, to slowly increase your ability to make sense of increasingly abstract ideas. Over time, as your experience and intuition grow, the whole curve moves away from the origin.

So if you feel lost at first — that just means you’re exactly where you’re supposed to be.

A lot of students who excel at math in high school end up pursuing computer science or engineering in college. Only a few continue down the road of pure mathematics. It’s not because they aren’t capable—many of them are brilliant. So what causes this drop-off? Why does advancing in pure math feel so much harder than expected?

To understand that, we need to think about how we learn, not just what we learn.

Imagine that learning is like playing a game. Each new concept is an enemy you need to defeat. In high school, the “defense stats” of math problems are relatively low. You can attack them with the standard moves—memorized formulas, pattern recognition, step-by-step procedures—and make steady progress.

But in pure math, the material gets denser, more abstract, and harder to penetrate. It’s like facing enemies with high armor: your usual attacks (rote learning or surface-level understanding) don’t do much damage anymore. At some point, unless you use special effects, you can’t even scratch the surface.

That’s the real shift. It’s not just that math gets harder—it demands a completely different style of play.

These “special effects” aren’t magical powers—they’re skills and habits that help you make progress when the usual tools no longer work. Here are a few that matter most:

Pure math isn’t just “harder math”—it’s math with higher armor, denser defenses, and fewer obvious entry points. It asks you to level up your approach. You can’t brute-force your way through with memorized techniques. But if you’re willing to develop new strategies—to sit with confusion, talk through ideas, make the abstract concrete—you’ll find that even the most intimidating ideas can be cracked.

And when they do crack, when the armor breaks and the idea finally lands—that’s when the game becomes really fun.

The dimension information is lost from the screen on your phone but the size of part of an art piece is what constitutes the impression the painting has given you. For example, It’s like I have seen the picture of mona lisa thousands of times before I actually goto louvore’s museum to see the actual one. When I finally got to the exhibition rooms seing the mona lisa so small sitting in the center of the big room the impression and feeling I received from it is completely different from what I got by merely looking at a picture.

When applying the probabilistic method, it is very common to get a value in the form . Such form can be hard to deal with. One can simply use the bound

, which is very good when

is very small.

When doing probabilistic method, it is common to obtain some bounds with binomials. Even though some time we can always use Stirling formula but the common bound you found in the google search is not as good for computation.

Here is the really useful bound: .

Furthermore, for Stirling approxmation for factorial, sometimes it is just have a pretty tight upper and lower bound. For example, we have .

It might not be obvious to the beginners. There are several implied assumption for mentioning the open problems.

As a result, whenever you show the open problem, it is a convention not only knowing the problem is open but

There are several important axiomatic properties about problems in mathematics.

Then, we have several corollary

This is my current thought, subject to future addition.